From Hardware to Software-Centric Paradigm

Introduction: Two Bold Statements

People often say, “The robots are coming.” In reality, robots have been here for quite some time. They have made our cars for decades already. What I think requires far more attention, though, are two trends that are two sides of the same coin:

- The industry of industrial robots is undergoing a paradigm shift from a hardware-centric to a software-centric paradigm.

- The robot itself is losing its role as the primary market differentiator.

For decades, industrial robots have been defined by four key metrics: speed, precision, reach, and payload. “Recently” (20 years ago), a robotic startup named Universal Robots entered the market by disrupting “a hidden 5th” which I will come back to. However, increasing competition from low-cost producers and a stronger push for digitalization are inevitably steering the industrial robot market toward a new paradigm, where these five hardware-centric metrics take on supporting roles. Moving forward, software will play the key role.

Understanding Paradigm Shifts

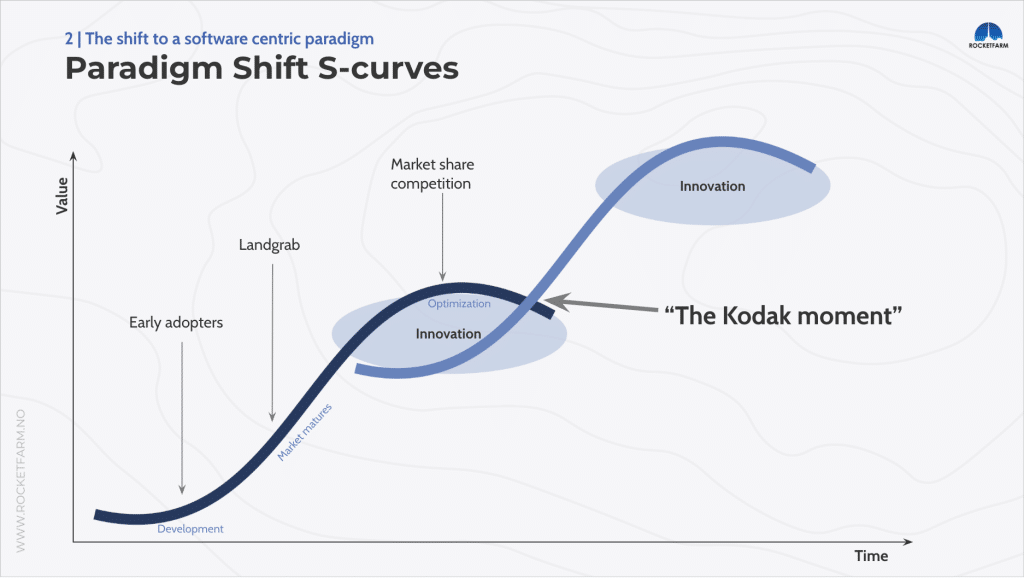

A paradigm shift is more than a new tool or process; it’s a fundamental change in thinking that can happen on any scale, from sweeping societal transformations to niche industry shifts. Think of the leap from barter to currency, or from printed maps to real-time GPS navigation. These shifts reframe entire industries.

A useful model here is the S-curve of innovation. A new paradigm starts slowly, picks up traction, peaks, and then saturates. At the same time, a new curve begins to form, often overlooked, misunderstood, or rejected by the incumbents. Eventually, the new paradigm delivers more value to the market than the old. This overlap is where industries are reinvented or left behind.Kodak, for example, invented the first digital camera, yet failed to become a significant player when the paradigm shifted to digital. For several reasons, this cost Kodak everything. Personally, I like to call this “the Kodak moment”, when a company fails to leap to the next curve and is overtaken by those who do.

Characteristics of a Hardware-Centric Paradigm

Before diving into it, it’s important to explain what I mean by a hardware- and software-centric paradigm and the characteristics that define it.

In a hardware-centric world, value is primarily measured by physical metrics. The hardware is the product, and everything else, including software, plays a supporting role. Sales conversations are focused on quantifiable capabilities like power output, battery capacity, megapixels, RAM, speed, and similar specs.

Software in this world is expected to be “good enough” to let the hardware do its job. It is typically proprietary and is the hidden enabler, not the differentiator.

Characteristics of a Software-Centric Paradigm

In a software-centric paradigm, this hierarchy is flipped: software becomes the main differentiator, and hardware exists mainly to deliver software-driven value. Instead of asking “How fast or strong is the hardware?”, the market asks “What can this system do?”, which concepts it supports in terms of features, services, and experiences.

Metrics shift from raw mechanical specs to value-added capabilities like:

- Plug-and-play integration

- Ecosystem compatibility

- Cloud connectivity and real-time data access

- Customizable workflows and APIs

- User-friendly interfaces

In this world, the hardware is no longer the differentiator! It is still essential, but it becomes a platform for delivering software concepts.

A Familiar Pattern: Past HW to SW-Centric Paradigm Shifts

The shift from HW to SW-centric is not something new and has happened in key digital industries before. Two key indicators that a shift may be on the verge:

- The HW metrics are saturated in the market, meaning that you don’t really get more bang for the buck by improving the HW-centric metrics, like megapixels in a camera. Eventually, adding more megapixels ceases to make a noticeable difference. Then, the focus shifts to concepts like “smart zoom”, “filters”, and “auto contrast”, which are software-centric features and concepts.

- The market is flooded with similar offerings. Low-cost copycats are optimising solely on the key selling metrics, making it harder for the quality-focused providers to stand out in the crowd. If you have not built a brand associated with quality by now, it can be hard to compete on quality over price.

Although several examples can be presented, let’s look at a couple of familiar ones:

Phones

In the late 90s and early 2000s, Nokia reigned supreme with small, robust phones with a good battery. You could personalise your phone by changing the cover and play Snake. Then, at some point, it seems Nokia’s strategy was to flood the market with an enormous number of Nokia variants as a means to fight off competition. Then the iPhone arrived, not just with a new form factor, but a new software paradigm. The App Store, GPS navigation, photo filters, and software-based UX transformed what a phone was. It had concepts that became differentiating in the market. Concepts that today are must-haves. Imagine owning a smartphone without an app store for 3rd party apps?

PCs

To keep it short. Generally speaking, in the 1990s, PCs were judged by MHz and RAM. Those were the buying metrics, and you never had enough of either one. Fast forward to today, unless you are a hardcore gamer, these metrics are supportive, and it is your “probably-more-complex-than-you-think” use case that defines your choice. Just think of what the spec is for your next PC. Chances are, MHz and RAM are not the first that come to mind.

Introducing Universal Robots

Now back to robotics! Having worked with Universal Robots for more or less my entire professional life, I find their journey a great way to explain why we are at the time of a paradigm shift.

The company was founded in 2005 with the new concept of cobots, collaborative robots. Which meant they could safely work next to humans. By doing so, they disrupted a HW metric, which was well known, but not yet market differentiating: AREA FOOTPRINT!

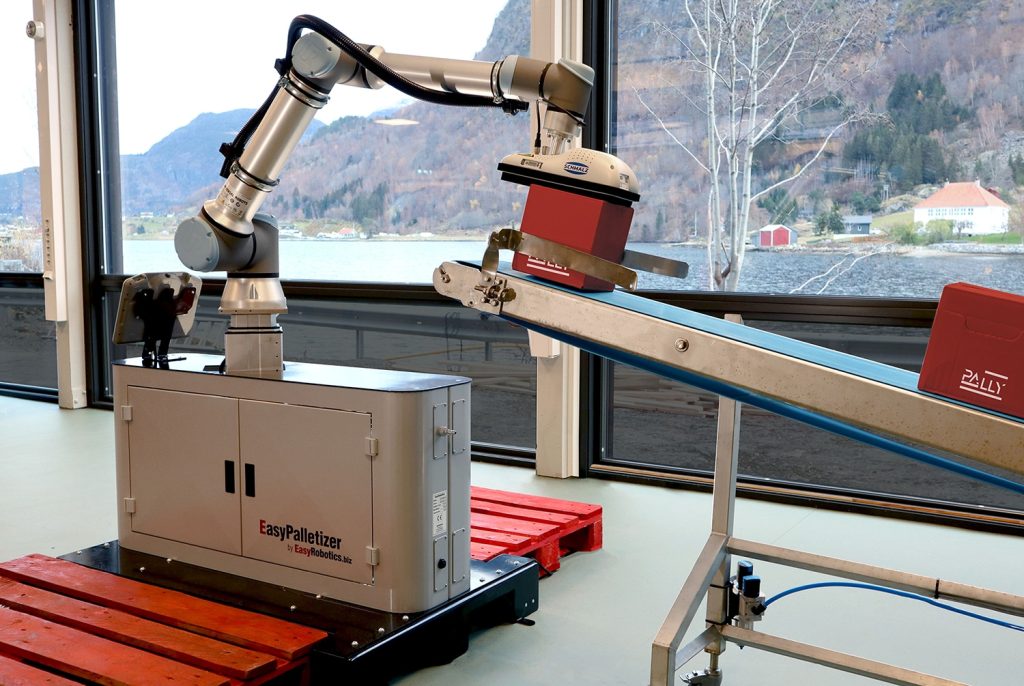

Robots, until this point, needed a huge amount of space due to safety fencing, making it more or less impossible to retrofit them into existing production lines. With cobots, you could. Recalling the first palletizing robot we worked with on a UR robot back in 2015, the spec was very clear: “We want a robot to palletize our products, but we have less than 1 square meter available for the robot.” A traditional industrial robot was not an option.

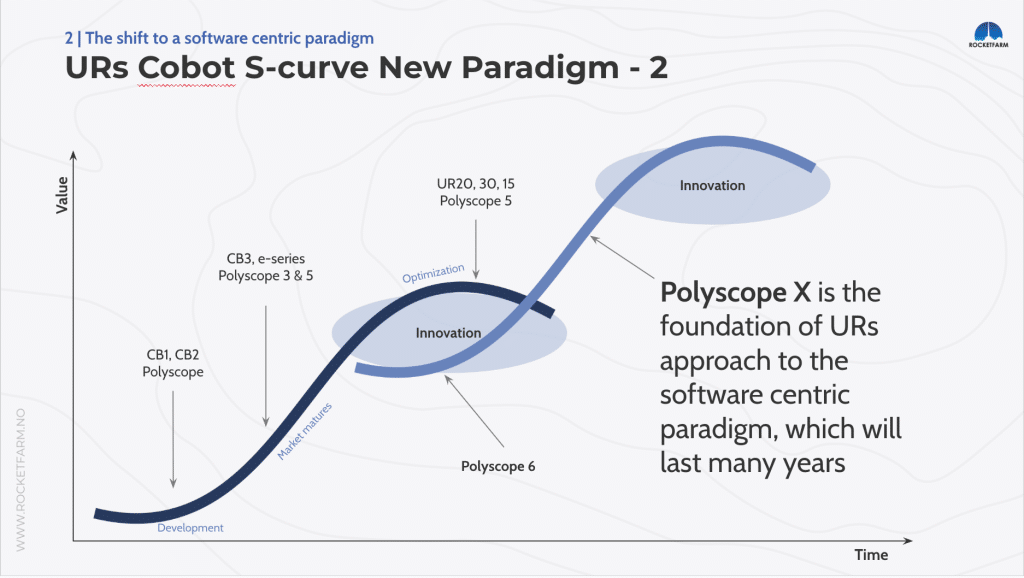

A Dive into the Collaborative Robot S-Curve

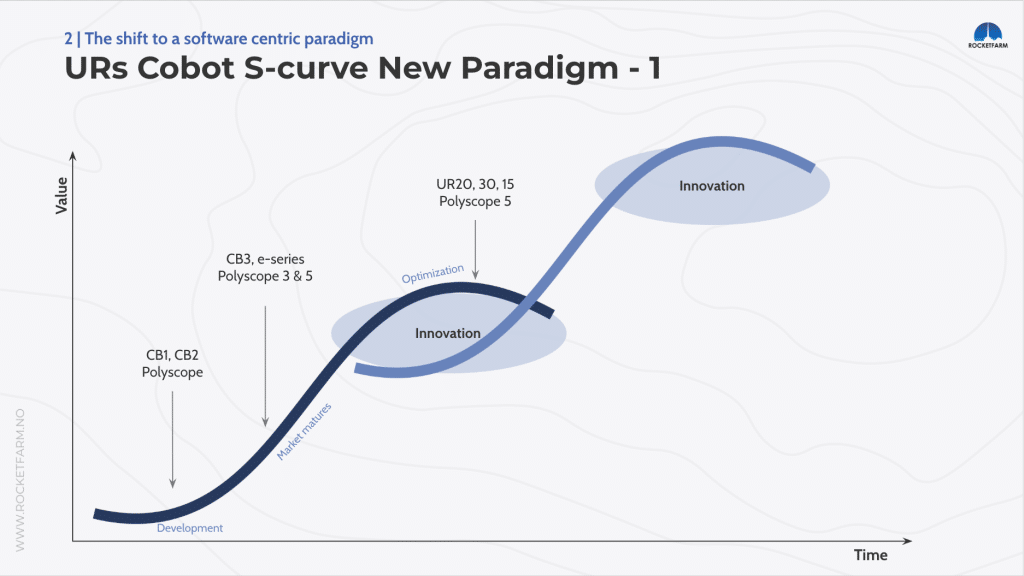

In its beginnings, UR, and thus the entire Cobot market, was in its development phase with the CB1 robot and its Polyscope operating system. This development stage of the S-curve takes time! When we, the team in Rocketfarm, got our hands on our first UR robot in 2012, 7 years after UR was founded, the total amount of UR robots in the market was still less than 1000.

As UR grows with improved robot versions, cobots slowly gain momentum. Although still a small portion of total industrial robots, UR holds a solid 50%–70% market share within the cobot segment. With UR’s CB3 and corresponding Polyscope 3 OS, the product had overcome many early-stage problems and gained momentum fast. But, as the market matures, competitors started showing up. Traditional big robot players like Fanuc and Kuka enter the field, but also many new cobot vendors who want to join the party emerge. The market is still a “blue ocean”, with “a landgrab” mentality of getting cobots to new customers buying an industrial robot for their very first time. The S-curve is now in its growth phase.

With numerous new players entering the field, the battle for distribution is intensifying. Pricing and margins are being squeezed, and currently, in 2025, we are at the point that whether you win or lose a project as a robotic solution provider can simply be because another provider was 5000 dollars cheaper. Robot installations (solutions) are becoming equally similar, hence 5000 dollars may be the only real differentiation you can see from a customer perspective. If you are new to robotics, buying your first robot, and understanding the important small differences can be hard. So why not save 5000 dollars? The S-curve is now in its saturation phase, where:

- The market is flooded with copycat competitors from low-cost regions.

- Differentiation based on physical metrics is eroding.

- Margins are tightening.

- Regulation is rising.

- Little value is left in incremental improvements.

Industrial Robotics at the End of Its HW-Centric S-Curve

Now, back to my introductory statement. The robot itself is losing its role as the primary market differentiator. You may wonder, how does the cobot S-curve translate so easily into the industrial robot S-curve? What is also interesting is that at this point in the cobot S-curve, the industrial robots have found other means of reducing their footprint, too. Safety scanners, together with other safety measures, have, for many purposes, been able to replace the safety fencing, closing the footprint gap between collaborative robots and industrial robots. Additionally, for those claiming that an easy programming interface was equally important for UR (more on that in another article), easy programming interfaces are emerging in industrial robots, too.

Similarly, the cobots have been closing the gap on speed, precision, reach, and payload in important market segments that do not require “heavy-duty robots”. Now “cobots” reach close to 2m, can pick 30kg+ and, as an example, can palletize 30 products/minute, which is fast even for traditional robots. In other words, Cobots and industrial robots are converging. Although they still differ greatly in maximum technical capacity, they share the same market destiny at the close of the hardware-centric paradigm.

The Rise of Software-Centric Robotics

For the long-lasting giants in industrial robotics (ABB, Fanuc, Kuka, Yaskawa), this shift is not “shocking” in any way. At this year’s Automatica trade show, software concepts played a major role. The major players are aware that to stand out in the growing crowd of copycats, enabling software concepts for the robots is the way forward to stand out in the crowd.

Examples of software-centric concepts that are gaining ground, and early signals that the next paradigm is already taking shape, include:

- AI is dramatically changing what the robots are capable of for a decent price.

- Web-based Human-Machine interface. Coding for the modern robots is now available for “all” who know how to build a web page, potentially enabling a much broader ecosystem of developers.

- Usable digital twins for verifying production changes up front with less downtime.

- Connectivity from the robot to “easily accessible” data storage, like the Cloud or internal robot management systems.

- Predictive maintenance systems.

- Remote support enables accessibility to the robot “experts” from anywhere, dramatically increasing the support reach of solution providers and 3rd suppliers.

- Robots as a Service concepts, where a variety of the above will dramatically improve the offering, are growing.

- A wave of excitement for humanoid robots. Not a topic for this post, but no doubt the humanoid euphoria emphasises the software-centric mindset in robotics in general.

What Software-Centric Robotics Requires

Coming back to the Universal Robots story. UR’s recent release of Polyscope X is good proof that they have recognised the importance of differentiation through software. But as paradigm shifts can be painful for many, so also for UR. What was supposed to be their new operating system, Polyscope 6, was developed, promised to the market, but never released. It’s hard to call this anything but a market failure. However, seen in the light of Polyscope 6 being a lesson where UR learned and developed important concepts for the software-centric paradigm, it may have been a necessary development step for Polyscope X.

The reason for coming back to the robot OS as such an important piece of the paradigm shift is that, in order to support the software-centric paradigm, robot manufacturers must be able to support concepts that previously have not been normal for them to support. To stop acting as hardware vendors and start behaving like platform enablers, the robot OS and interface perspective must have dramatically improved support for APIs, native web tech, real-time data, built-in cybersecurity, and safe third-party extensibility, to mention a few.

Said differently: New robot operating systems are finally giving third-party developers the tools to create transformative robot software.

Cyber Security as a Driving Force for Change

One additional factor accelerating the shift is regulation, most notably the EU’s Cyber Resilience Act (CRA). And for those of you who think this only applies to robots connected to the internet, think again. A requirement we hear more frequently these days is that robots relying on USB sticks for data transferring are not allowed on site, as cyber risks also come “from within”. By the end of 2027, CRA will require cyber security to be incorporated by design in all connected products, including industrial robots.

This is not a trivial update; it requires rethinking robot system architecture, data handling, and update delivery. Many manufacturers will need to overhaul their hardware–software integration to meet these requirements. Since cyber resilience is fundamentally a software-driven capability, the regulation essentially pushes the industry further into the software-centric paradigm, making secure connectivity, update mechanisms, and robust code design a baseline expectation rather than an optional extra.

So if you are about to buy your first robot, make sure you ask the question if the robot is compliant with, or can easily be upgraded to comply with, the required cyber security standards.

Conclusion: Are We Past the Kodak Moment?

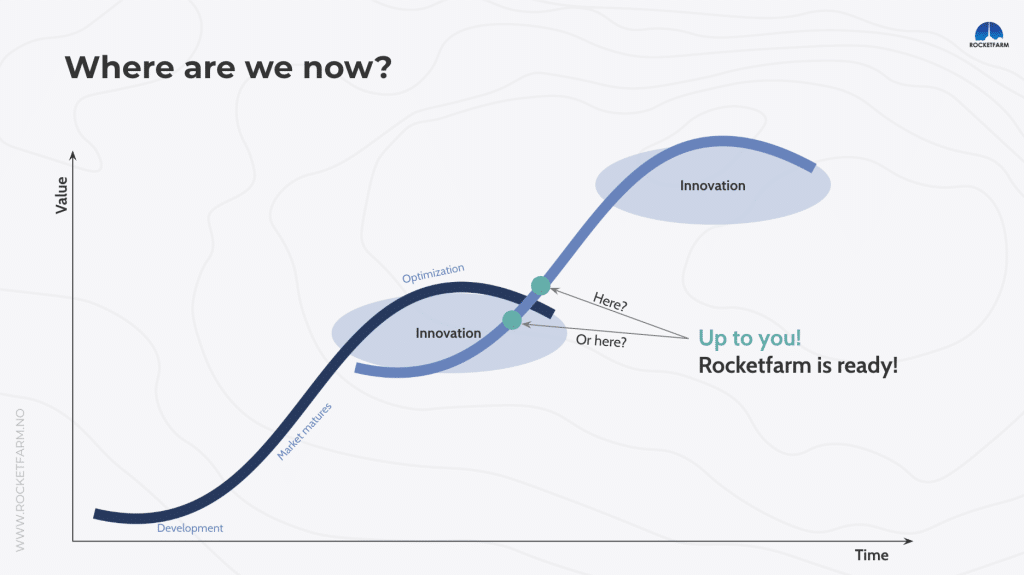

Looking at the current trajectory, one might ask if the robotics industry has already experienced its own “Kodak moment” – that point at which the warning signs were clear, the next paradigm was emerging, and yet many players hesitated to adapt. In my view, we are right on the brink of that moment now.

For us at Rocketfarm, a 3rd party software developer in robotics, the new OS from players like Universal Robots with Polyscope X and Doosan’s Dart Suite makes us finally capable of building transformative robot software that enables new market concepts. For us, it enables us to combine the strengths of our two flagship Pally palletizing software solutions and MyRobot.cloud as a robot management system.

Eventually, I believe it is within this new software-centric paradigm that we will see the robot “killer apps” (sounds much worse for robots than for PCs…), maybe being capable of solving the “holy grail” of industrial robotics, which is… More about that in my next article 🙂

Are you ready to explore the many possibilities in cobot palletizing?

Let’s talk – get in touch today!